Following our initial research into the impact of COVID-19 on the care home sector in England, we have updated these findings to take account of new data published within the past fortnight.

Director, Ben Hartley, talks about the key changes and explains why we will continue to monitor the data throughout the pandemic.

The first point to stress is that while our analysis is an academic and business exercise, we remain acutely aware of the human cost behind the figures and acknowledge the extraordinary difficulties experienced by care home residents and their families, as well as by operators and carers delivering front-line services.

Media and political scrutiny remain intense and it would be easy to use our findings to attribute criticism or praise. But the job of the analyst is to be dispassionate, to present the facts and to let the conclusions speak for themselves.

The following new data has been included in this report: –

- 2 additional weeks of actual death rate data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS)

- ONS registration data released on 19 May which, allowing for a circa two-week lag, takes us to 8 May

- New ONS, CQC & NHS data sources to assist in predicting trends.

This data, combined with some revised assumptions, has produced three important changes from our original findings: –

Fewer excess deaths

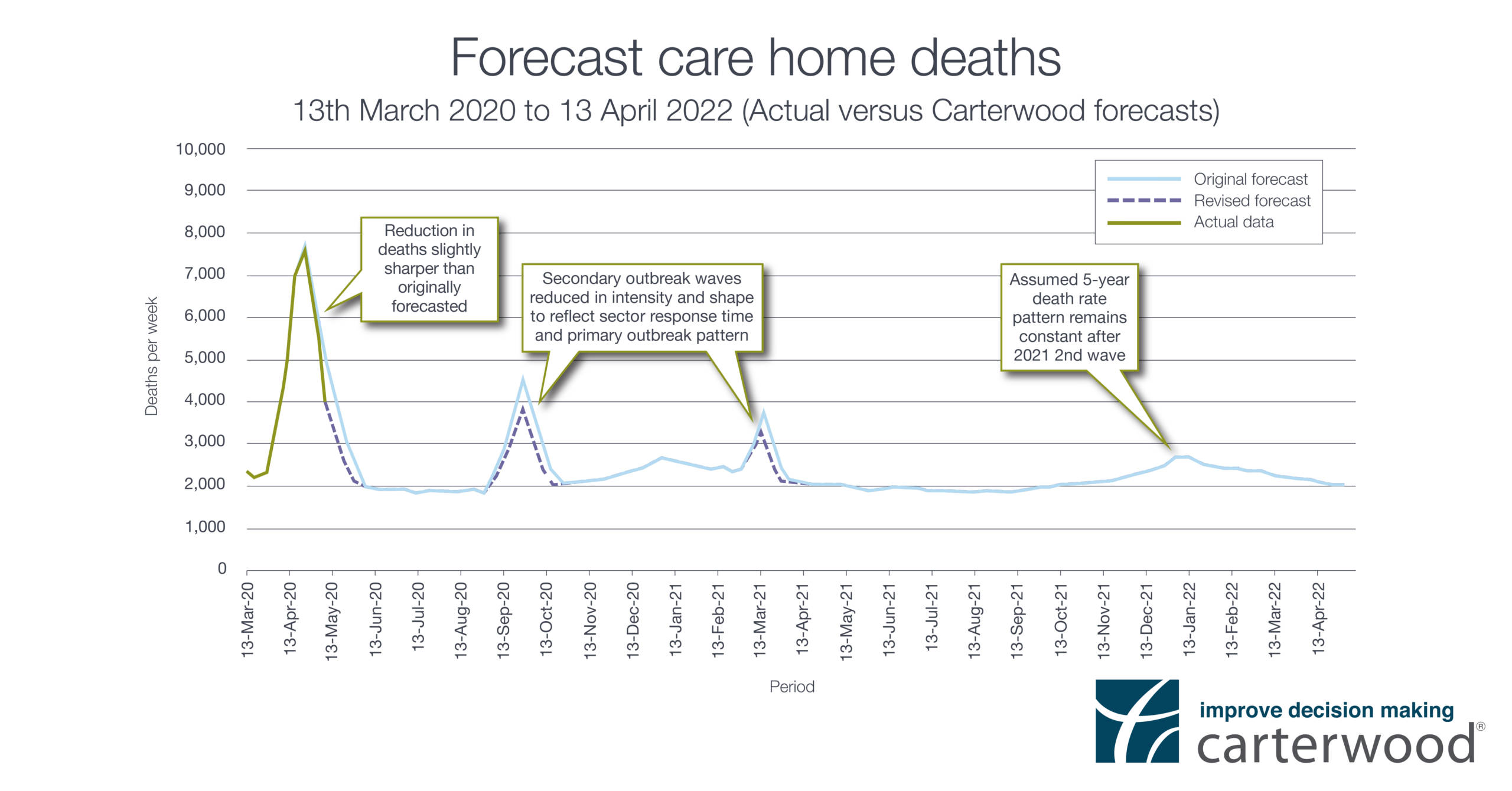

Forecasted excess total elderly care home deaths during the COVID-19 outbreaks (to April 2021), when measured against the 5-year historic average, have fallen from a predicted 36,442 to 30,635.

In essence, this change is explained by a predicted fall in the intensity of subsequent COVID waves than was originally anticipated. The sector, and rest of the world, was very much caught ‘on the hop’ in March. We believe that, due to the impact of improved protocols, equipment supplies, self – isolation and widespread testing, these future outbreaks will be more manageable and the increase in deaths slightly lower than originally forecasted.

In addition, errors, like mass discharging from the NHS into care homes without testing, will not be repeated.

Increased rate of care home closure

Our original model assumed a loss of 1,000 beds per month (twice last year’s annual average) during 2020, with 600 per month thereafter. Our latest iteration raises the 2020 monthly loss to 1,500 beds (three times last year’s annual average) taking account of staffing issues such as mass testing, workforce enforced self-isolation and huge projected increases in agency costs, all of which will affect viability and drive closures. Post 2020, the predicted monthly loss of 600 beds remains.

There are other factors which will affect the bed loss rate.

Some larger operators may well use COVID as a “smokescreen” to speed up the closure of “uneconomic assets”. Highly geared operators, without strong balance sheets, may struggle to meet debt covenants and find investors and funders unprepared to support them, whilst some smaller operators, without fully market compliant care homes and lacking the insulation of a larger group structure, could find that additional cost pressures erode their already tight margins, leading to closure.

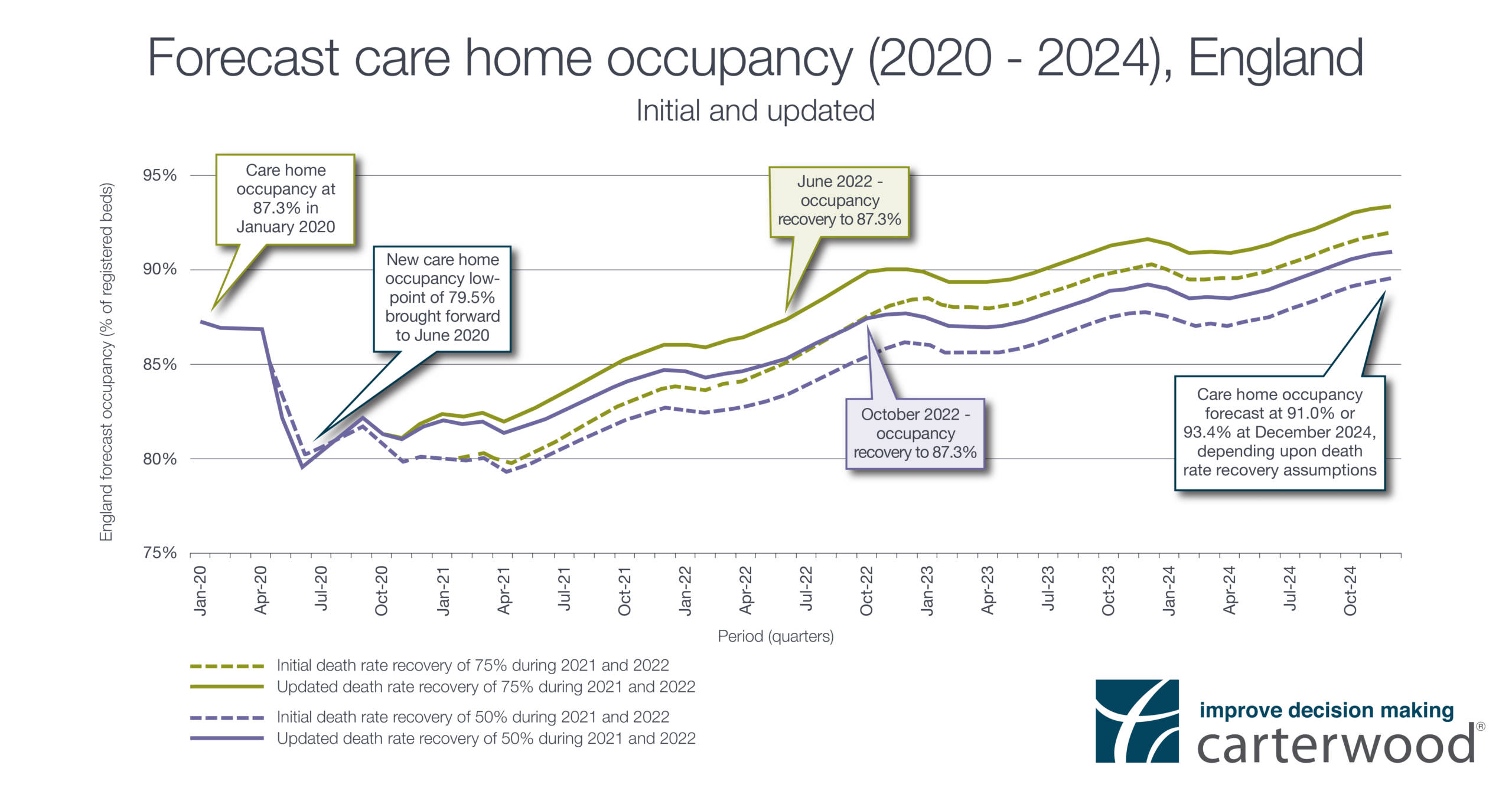

Earlier return to pre-pandemic occupancy levels

The occupancy low point, predicted as being 79.3% in April 2021, will be marginally higher at 79.5%. It will also arrive much sooner, in June 2020 rather than April 2021, a result of the updated assumptions and data outlined above.

Furthermore, our original report forecast that occupancy would return to the pre-pandemic level of 87.3% some time between October 2022 and September 2023. This level is now predicted to be achieved slightly earlier – between June and October 2022.

Forecasts and predictions

We all know that predicting the future is challenging, but based upon our assumptions, the analysis also points to the following issues which warrant further consideration.

Quality of stock

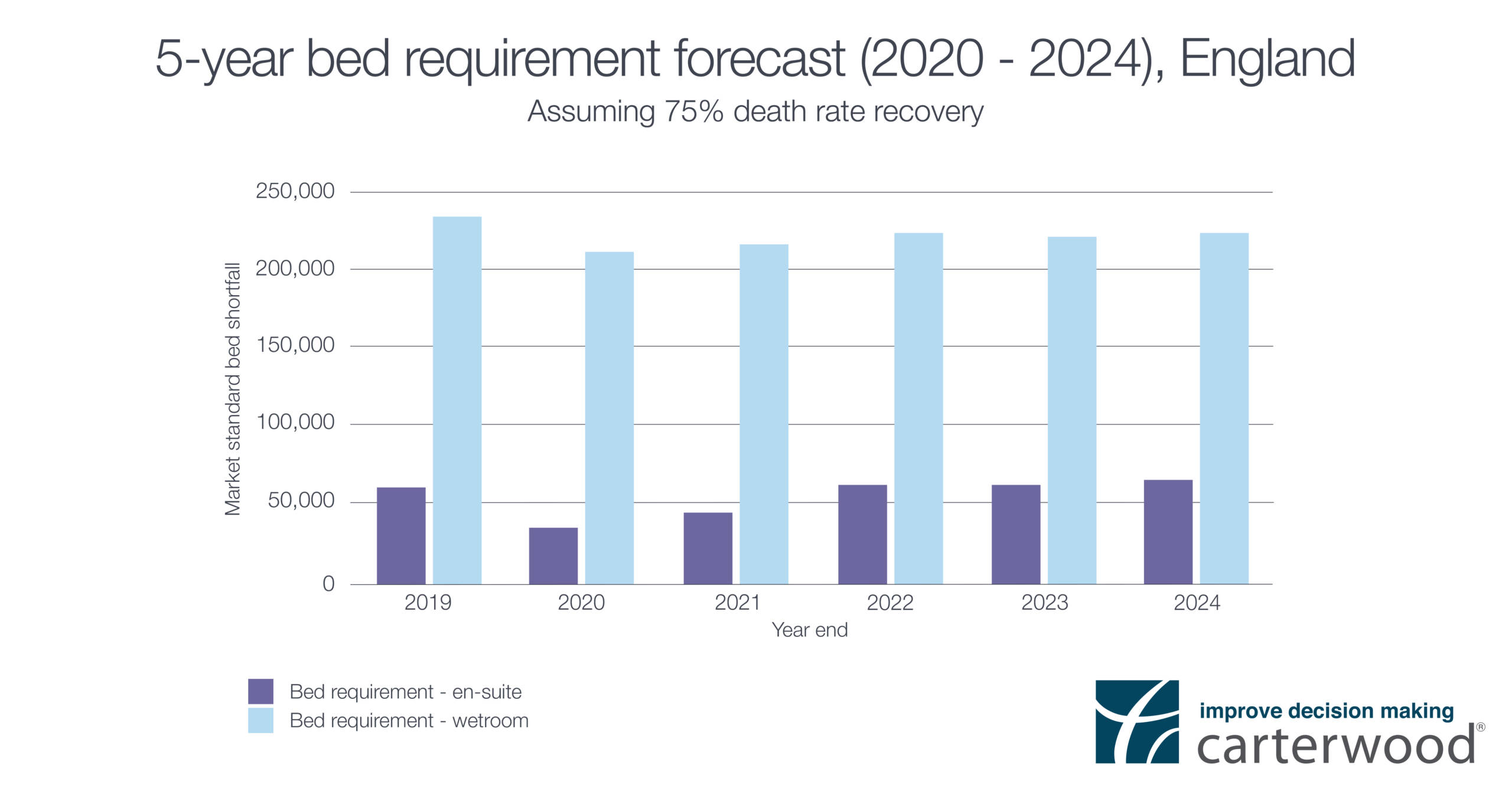

Not far short of one third of the beds in England (29.5%) are not “market-compliant” i.e. without en-suite WC and wash hand basins.

In a post-COVID era, market expectations (both self-funded and local authority) are likely to rise and the effectiveness of a care home to enable residents to effectively self-isolate will be called into question.

It remains to be seen if there will be any regulatory changes to spatial/environmental requirements for care homes and any changes are likely to take some time to work their way through the system. Nevertheless, homes with level access wetrooms are the only accommodation option that enable the washing and bathing elements of self-isolation to be carried out over a meaningful length of time. The graph below shows the extent of the shortfall of wetroom accommodation, which makes for a strong case for investment in the sector.

Self-funding market

Higher fees and greater profitability mean the private market is likely to be better insulated to withstand any short-term occupancy dips than providers operating on much tighter margins driven by local authority fee rates.

Although all homes are virus targets, high quality accommodation allows residents to more effectively socially distance and thereby minimise the risk of outbreaks. There may even be potential for private operators to charge premium fee rates for ‘COVID-free’ environments.

Data about resident recovery within care homes will be critical to help restore confidence that outbreaks can be managed. The potential reputational damage of the crisis cannot be ignored and winning back public confidence will be critical in determining the speed of new admissions.

Anecdotal evidence and hard data reinforce our view that COVID outbreaks and severity will vary considerably from home to home and from region to region. Highly localised work will be needed to understand the true impact for individual areas.

Drawing conclusions

It might be a truism to say that “the only certainty is uncertainty”, but this has been a period like no other in living memory. Information will continue to percolate through and this will affect not just forecasts and predictions, but will also teach us lessons and direct us for the future.

Sources: ONS, Laing Buisson, Public Health England, Tomorrow’s Guide, World Health Organisation and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.